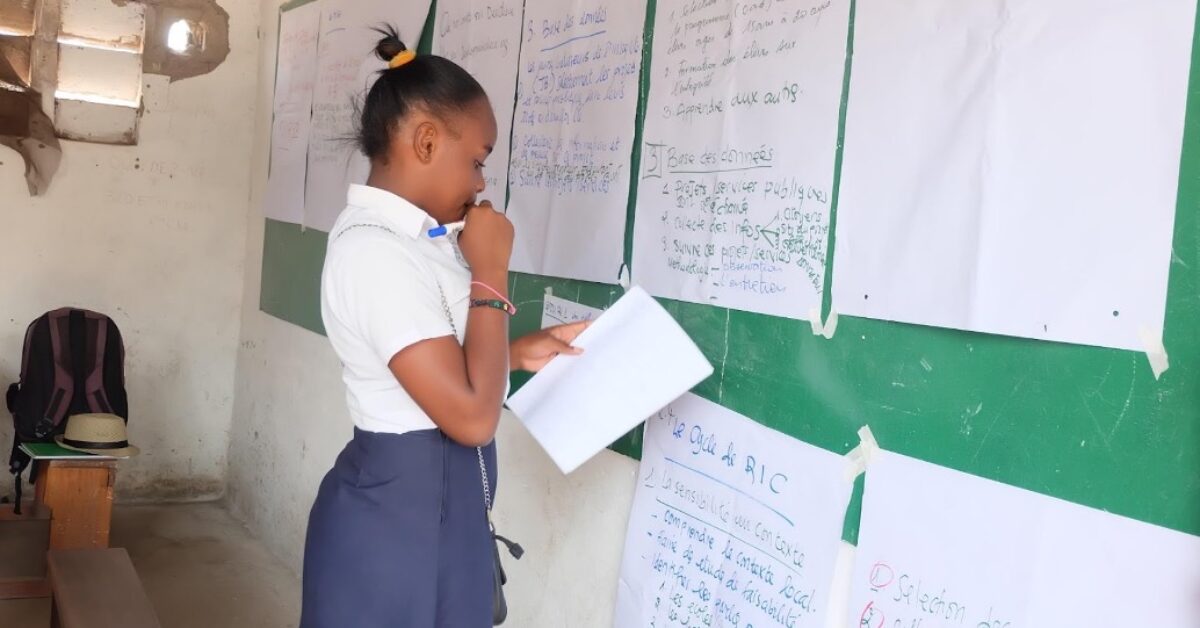

In 2017, CERC established 54 Integrity Clubs in South Kivu to empower 810 students aged 14-19 to learn about Integrity and monitor projects and services in their community, including their schools. They used our technology tool “EduCheck” to report issues and fixes.

US-DRC Strategic Minerals Partnership: What Monitoring Mechanisms to Prevent Corruption?

A strategic partnership between the United States and the Democratic Republic of Congo is currently under discussion. This partnership represents a historic opportunity to strengthen bilateral economic cooperation and promote sustainable development, particularly in the mining sector, which is vital to global technology and energy industries.

Major US companies such as KoBold Metals and AVZ Minerals have already expressed interest in this emerging partnership with the DRC. Their involvement could pave the way for:

- massive foreign direct investment;

- job creation and local skills development;

- infrastructure modernization;

- the introduction of good environmental and social practices in mining;

What mechanisms are in place to ensure transparency and monitoring of the strategic minerals partnership between the US and the DRC? More specifically, what role can play Congolese civil society in promoting accountability?

The issue of monitoring new contracts and investments, such as those involving KoBold Metals and AVZ Minerals, is crucial to ensure that they contribute to sustainable development and do not exacerbate inequalities and corruption. This is all the more important given that the DRC’s mining industry is historically vulnerable to corruption, contract mismanagement, and political influence.

A History of Repeated Challenges

The DRC is rich in natural resources, but the history of the extractive sector is marked by opaque practices, poor contract management, high-level corruption, and largely non-existent local development. Too often, big promises of foreign investment fail to translate into improved living conditions for local communities or structural transformation of the economy.

That is why transparency, accountability, and citizen participation must be at the heart of this new strategic partnership.

What Monitoring Mechanisms Can Prevent Corruption?

1. Contract Transparency and Public Oversight

The DRC is a member of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), which requires the publication of mining contracts, revenues, and the actual ownership of companies. However, implementation remains weak. Civil society organizations, such as CERC, have a vital role to play in monitoring compliance with transparency obligations, particularly at the local level where mining takes place.

2. Independent Monitoring by Civil Society

The ability to conduct independent assessments of mining revenue management and the implementation of social commitments made by US companies is something that CERC is capable of. Thanks to its strong presence in eastern Congo and its dynamic network of young people trained in social accountability, CERC is well placed to highlight discrepancies between promises and the reality on the ground.

3. Active Participation in Governance Spaces

Civil society participation mustn’t be limited to observation. CSOs must be integrated into monitoring committees and contractual negotiations. Their expertise can help assess environmental and social impact reports, verify the implementation of local content obligations, and ensure that affected communities are genuinely consulted.

4. Digital Tools to Fight Corruption

CERC can deploy civic technologies such “Citizen Eye” to collect corruption reports, monitor procurement processes, and detect failures in project implementation. By training citizens, youth, and community leaders on these tools, we can build effective early warning systems.

5. Legal Empowerment and Advocacy

CERC is also committed to strengthening the legal capacity of communities so that they understand their rights in the mining sector and can hold US and DRC companies accountable. Through our expertise in civic education and human rights, we contribute to structured, evidence-based advocacy.

6. International Support and Institutional Recognition

For CSOs to be effective, they must have adequate funding, legal protection, and technical support. International partners, particularly those involved in the US-DRC Partnership, should formally recognize the role of organizations in governance mechanisms and allocate resources to support their work on the ground.

The strategic partnership between the DRC and the United States on critical minerals can be a lever for real transformation, provided that it is governed with integrity, transparency, and inclusivity. CERC stands ready to play its role as a citizen watchdog, mobilizing youth, local communities, and institutions to ensure that this new investment dynamic is synonymous with social justice, local development, and sustainability.

We call on the Congolese authorities and their international partners to integrate civil society in a structural manner into this process. In this way, the DRC’s natural resources will cease to be a curse and become an engine for a shared future.

Author : Heri Bitamala, +12062223388

Training to Transform: CERC and ACAJ lead anti-corruption efforts in Kinshasa

Corruption continues to slow down national development, erode public trust in institutions, and deepen social inequalities. Through this training, the two organisations aimed to raise awareness on the root causes of corruption and provide participants with practical, legal, and ethical tools to prevent, detect, and fight it effectively.

Fighting Corruption in Schools: CERC and APNAC DRC to propose Legislative Initiative to the National Assembly of the DRC

CERC is launching an ambitious initiative to build integrity and anti-corruption measures in the education sector. This initiative takes the form of a Draft Law aimed at incorporating Integrity Clubs and an Integrity Education course in all secondary schools across the country.

CERC, an organization dedicated to promoting integrity and transparency, developed this proposed law in collaboration with Members of Parliament (APNAC DRC), education experts and civil society actors.. The primary objective is to raise awareness among students from a young age about the principles of integrity, civic responsibility, and anti-corruption efforts.

In 2022, the African Parliamentarians Network Against Corruption (APNAC RDC) endorsed this initiative at the DRC National Assembly. These parliamentarians, fully cognizant of the dire consequences of corruption in education and on the nation’s progress, have taken the initiative to champion this Draft Law and transform it into actionable legislation.

The Integrity Clubs outlined in this proposed law will be dynamic structures within schools, composed of elected students tasked with promoting integrity and transparency. Concurrently, the Integrity Education course integrated into the regular school curriculum will educate students on ethical issues and civic responsibility.

This initiative represents a major step forward in the fight against corruption in the DRC, as it aims to instill integrity values from an early age and mobilize students as key actors in this struggle. It also aligns with a broader effort to strengthen institutions and promote good governance.

CERC and the parliamentarians who are members of APNAC RDC call for widespread support from the population and civil society actors to make this proposed law a concrete reality. Together, we can work towards a future where integrity and transparency are the cornerstones of our education system and society as a whole.

The Illicit Financing of Political Parties: A Serious Threat to Equity and the Integrity of the Electoral System in the DRC

The illicit and non-transparent financing of political parties poses a major challenge to the equity and integrity of the electoral system in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This practice, in addition to compromising the transparency and fairness of elections, erodes public trust in the democratic process.

Building Infrastructure with Integrity: The Role of Citizen Monitoring and Advocacy

Corruption has been a longstanding issue in the DRC, particularly in infrastructure projects funded by international aid and public resources. These projects, vital for economic development and improving citizens’ quality of life, often face corruption at various levels, leading to cost overruns, substandard work, and delayed completion.

Tackling illicit financial flows from Africa for Africa’s economic development

Despite the proliferation of international, regional, and national legal instruments and mechanisms that regulate the issue of illicit financial flows, Africa struggles to reverse the trend against these scourges that bleed its economies and act as a bottleneck to its development. According to a report commissioned by the Conference of African Ministers of Finance, Planning, and Economic Development, produced by the high-level panel on illicit financial flows from Africa, the biggest obstacle to development financing in Africa is the problem of illicit financial flows. It is estimated that these flows amount to between $50 billion and $80 billion annually, surpassing the level of foreign aid received by African countries (Report 2015).

From 2000 to 2015, the total amount of illicit capital fleeing Africa reached $836 billion. Compared to the total stock of Africa’s external debt, which was $770 billion in 2018, this makes Africa a “net creditor to the world.” While Africa received $29.7 billion in official development assistance in 2018, it simultaneously lost over $50 billion in illicit financial flows. The large-scale illegal money movements each year prevent developing countries from having the necessary resources to progress and build basic public infrastructure for the population.

According to a joint initiative by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the World Bank’s Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative (StAR), between $20 billion and $40 billion are diverted annually by corrupt public officials in developing countries and transferred abroad. These amounts primarily come from diverted public funds or bribes received in relation to public decisions, such as awarding public contracts or obtaining permits. In cases of corruption, the payments to corrupt public officials often originate from foreign multinational corporations from developed countries. In addition, improper commercial invoicing, transfer of multinational corporations’ profits, and offshore banking deposits to conceal crime proceeds or evade taxes deprive national treasuries of much-needed resources that could be invested in development.

The adverse effects of corruption on the economies of African states are well known. Corrupt practices worsen poverty, reduce government tax revenues, constrain spending on health and education, discourage foreign direct investment, or stifle new business creation. Furthermore, they create a fertile ground for organized crime and terrorism. Unfortunately, a large portion of money acquired in the poorest countries is transferred and held abroad, often in the wealthiest countries, in the form of cash, stocks or bonds, real estate, or other assets.

While the sources of illicit financial flows are indeed within the continent itself, the mechanisms for channeling funds often involve non-African private and public actors and are sometimes the result of policies and laws adopted by intergovernmental bodies and governments of other continents.

In February 2010, Equatorial Guinea was targeted in a report by the U.S. Senate. Titled “Keeping foreign corruption out of the United States: Four case histories,” the report examines how Teodorin Nguema Obiang Mbasogo, son of the Equatorial Guinean president, used the services of American lawyers and real estate agents to introduce over $100 million of suspicious funds into the country and serve his interests there, including buying a $35 million villa in California and a $38 million private jet. The report notes that this is not the first time the Obiang family has been investigated by a U.S. Senate task force. Similar cases are widespread worldwide.

Developing countries, especially those in Africa, lack institutional and administrative capacity in measuring illicit financial flows, regulating them, and enforcing existing laws and regulations. Therefore, multilateralism has a key role to play in reducing illicit financial flows, which are among the most serious threats to the contemporary world. The rationale for asset recovery is that, for centuries, developing countries have suffered greatly from the loss of vital resources due to illicit outflows of their assets, thus depriving these countries of the resources needed for economic development, social well-being, and political stability.

The return of assets to their countries of origin, especially in Africa, can have a significant impact on education, employment, health, infrastructure, and overall development. Asset confiscation and restitution are powerful tools and a panacea for sustainable development prospects in Africa. The resource needs of African countries for the provision of social services, infrastructure, and investment underscore the importance of eliminating illicit financial flows from the continent.

Recommendations to the Conference of States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption to eliminate illicit financial flows from Africa:

To Africa’s partners:

- We recommend enhanced collaboration and consistent engagement between Africa and major global players such as the United States and the European Union to improve transparency in the international banking system, inviting banks to share necessary information about bank assets (identity, asset origin, and country of deposit and depositors).

- We recommend the IMF, the United Nations, the World Bank, etc., to assist African States in adopting measures and instruments to combat illicit financial flows and to place the issue on the global agenda, seeking greater coherence in the efforts undertaken for this purpose.

To African States:

- Strengthen genuinely independent bodies and administrations responsible for preventing illicit financial flows.

- Improve supervision of banks and non-bank financial institutions.

- Establish a mechanism for analyzing the nature and extent of illicit financial flows from Africa and disseminate information to the public to raise awareness of the negative effects of illicit financial flows from Africa.

- Develop mechanisms for sharing and coordinating information among various public institutions and administrations responsible for preventing illicit financial flows.

Author: Musa Nzamu ([email protected])